How “Flow” enters into Development Desgin

Original: https://eponline.com/articles/2010/10/01/part-2-prefurbia-incorporates-flow.aspx?admgarea=Features

This article was written by the planner of The Village of San Buenas.

Part 2: Prefurbia Incorporates Flow

- By Rick Harrison

- Oct 01, 2010

For the past four decades, the automotive industry has invested billions in fuel efficiency and reducing drag and, at the same time, significantly added to the average engine horsepower. While government has focused on the vehicle, no steps have been taken to make neighborhood streets more efficient.

The management of a new era of design dedicated to reducing time and energy while transiting through a neighborhood is called “flow.” In Prefurbia, flow is essential to neighborhood sustainability.

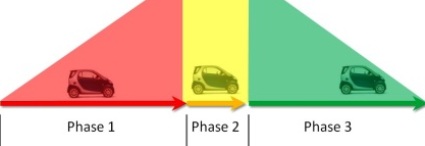

Getting a vehicle in motion (Phase 1), cruising (Phase 2) and stopping or slowing (Phase 3) are the three phases of a “segment cycle.” A segment begins upon entry to a street and ends when a driver stops or slows down to turn or enter another street. Phase 1 involves the time and energy needed to get a one- to two-ton (or more) vehicle moving from a stop to a target residential speed. In some areas, this could be from 20 miles per hour to 30 mph. Phase 1 consumes the most energy and typically the most time. Phase 2 uses the least time and less energy than Phase 1. Phase 3 consumes almost as much time as Phase 1, but with new braking technology, this phase can actually generate energy. Reducing the number of Phase 1 segments lowers the amount of energy consumed. Similarly, reducing the number of Phase 1 and 3 segments also shortens the time needed to travel.

At 30 mph, the distance needed to accelerate and then stop comfortably is about 400 feet.

In traditional planning processes, designers give little (if any) attention to the flow of traffic. Very few homes are located on an entry street, requiring 90 percent of the residents to travel a minimum of two segment cycles. About half the residents have to use three segment cycles to reach their homes. In Prefurbia, most residents can get home with just one segment cycle, and only a few others have two segment cycles.

The length of Phase 2 is critical. In the conventional subdivision, for the most part, the distance along each segment cycle is quite short with some so small that Phase 2 is never reached. This design may be so inconvenient from a flow standpoint that the driver is “encouraged” to accelerate to make up for the time. Segment cycles within the Prefurbia neighborhood are long, enabling a driver more time in Phase 2.

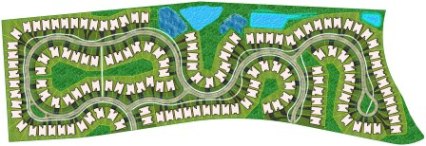

Note the cul-de-sac on the right in Figure 3. Why didn’t the designer reverse the street to loop the cul-de-sac the other way, reducing the segment length from the entry to the end of the cul-de-sac? Prefurbia is a balance of economics, environment, and existence so the designer must weigh each benefit and derive a design that serves each of the three “Es” well. In this case, the geometry of the area better achieves efficiency with the current configuration. Also, having an intersection serving 30 homes as soon as a driver enters the neighborhood is not the best for safety. On the other side of the site, there is such an intersection but it serves fewer lots. Finally, the cul-de-sac provides a nice entrance void of street intersections. The homes pulled away from the street give the impression of low density. If a street was placed at this point, entering the neighborhood would not have this welcome feel.

In Prefurbia, designers use [www.performanceplanningsystem.com/trafficdiffuers] traffic diffusers, which maintain flow on the primary traffic street while providing the functionality of a roundabout.

From a pollution standpoint – addressing the auto industry without addressing planning is like requiring frosting to have no calories yet use the frosting on a high fat, sugar laden cake

Reducing environmental impacts

Prefurbia reduces waste and employs more efficient forms of design. The method represents a reversal of how technology in land development is used, replacing lots per minute (LPM) automation with the art of neighborhood design. It’s time for technology to be used to construct great neighborhoods for families to thrive. By exceeding the minimums, designers can deliver economic and environmental advantages.

There are only a few situations in which a tight grid pattern designed to minimums is the optimum solution from a geometric perspective. Such a site must closely conform to the dimensions needed to stack lots, with a fairly flat topography and long blocks that have few cross streets.

Here are a few examples that demonstrate better efficiency gains through design.

Figure 1 shows two cul-de-sac’s side by side. Both use the following minimums:

- 25-foot front yard setback,

- 5-foot side yard setback,

- 80-foot lot width at the setback, and

- 60-foot cul-de-sac minimum radii.